It is the first Sunday of the month and several Iris Ministries churches have gathered together here at Zimpe

The first Sunday of each month always reminds me of the bigger picture of life here in Mozambique. You see, I live at a children’s centre behind guarded gates and high walls. Zimpeto’s 260 kids get three square meals and two showers a day and new clothes when their old ones rip; they receive an education; they grow up amidst the love and support of a community of believers. I live in a comparably well-off bubble slap-bang in the midst of a community so poor that many people right outside our well-guarded gates eat onl

On the first Sunday of each month, the “real” Mozambique visits for the morning. I sit near the old vovos – the grandmothers - in their traditional, vibrantly-coloured capulanas and head scarves, looking so much older than their years.

I cuddle a little girl on my lap whose skirt is held up with a safety pin and whose knees are scabby and weeping. Her big brother, perhaps nine or ten, stands next to us, his smile bright and his eyes sparkling with good humour even as his light hair and dull skin wordlessly reveal his malnutrition. While the music plays, his ripped, buttonless shirt flaps open and fa

The longer I live here, the more desensitised I become and the less I notice the poverty and its attendant suffering right on my doorstep. I no longer rage loudly at the injustices surrounding me but simmer quietly instead. Perhaps I have run out of words. Perhaps my heart grew weary from feeling too deeply, too often. Or perhaps, somewhere along the line, I decided to stop

A year ago I used to pray each Sunday with a young woman who was too sick to sit up in church. She would drag her emaciated body onto the back of our flat-bed truck, ride to church with others from the community, make it in the door then lie down, having expended all her strength to get there. Each week I would sit on the floor or on a bench and pray with her, flicking the flies away and desperately pleading for healing and life to flow back into her wasted frame. It has been a year now and, somewhere along the way, she stopped coming. I didn’t notice until today. How could I not notice?

Indifference is grey. It is dull and tasteless and it is deceptively powerful. I need the sharp stab of conscience to move me once more, to guide me, to have its painful way in the apathetic corners of my heart. If not, what am I doing here?

I want to carry with me always the jagged pain

The music ends and we all sit, my young friend with the buttonless shirt fingering my shiny new silver watch, entranced by its glossy exterior and by the hands moving within. To me it is a cheap watch, to him it’s worth a fortune. He glances at me with a huge smile, expecting me to pull my hand away. I don’t, and he is thrilled to be able to run his finger gently around the smooth glass. We both laugh and my heart begins to feel once more.

Suddenly there is a crash from the right

Two teenage girls from the community are called forward to sing. The African harmonies in their song make my heart sing with them. The beads in their hair click rhythmically as they sway, singing unaccompanied and with perfect pitch, the rhythm starting at their toes and working its way up until, towards the end, their whole bodies are moving, their eyes closed and their arms

And then it begins... Pastor Nico calls all the women and girls forward: it is Women’s Day, after all. The littlest girls rush to the front, vovos help each other off the floor, missionaries line up, the teenagers shuffle, embarrassed, and the visitors glance around, wondering if they’re included. I feel drab and dull in my black blouse and dark denim skirt as I kiss on both cheeks one of the vovos dressed in diverse patterns of greens, blues and reds. I wish her a “feliz Dia das Mulheres” – happy Women’s Day! I’m proud of myself for saying it so fluently in Portuguese then remember that she only speaks Shangaan. We smile and hug, sharing the language of celebration instead, our womanhood bonding us despite differences in age, cultu

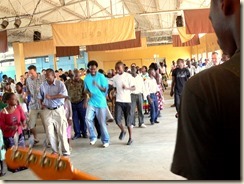

All the men and boys form two lines facing each other along the front of the church, then out the front door, up the long footpath and in the back door. They raise their arms and hold hands to form a tunnel, the littlest boys reaching to raise their arms as high as they can.

The music plays, the drums beating out a rhythm as my vovo friend sways in time, elbows bent, her arms swinging steadily as if to propel her forward. She bends low to walk into the tunnel and I follow.

Hands touch our heads as the men pray for us, hands on our backs and shoulders, hands pulling us forward, hands pressing us through. This is no time to be sensitive about one’s personal space. I feel my hair clip fall and don’t care: there are some moments in life when messy is good and this is one of them. My back aches from bending low as we pass the small boys, laughing as they mess up my hair on purpose. I laugh with them.

It is hot, sweaty work, making our way through that long, long tunnel. It is loud and joyous as we stop and start, shuffling slowly and getting completely mussed up. As we exit, everyone is laughing, hugging, kissing cheeks and high-fiving (yes, even here).

I sit down, still chuckling at the chaos and the noise and the bodies bumping up against each other and at how untidy I now am, and I’m thankful. Perhaps this morning is a gift to remind me that, while sharing in the suffering of others, one must remember to also share their joys.

We celebrate together and perhaps the bright, colourful, patterned clothing of the Mozambican vovos can teach me a thing or two about the colours of life here.

Perhaps the joy of dancing through a tunnel of hands fills them with the strength they need to get t

Perhaps they need my laughter more than they need my tears and this is a gift I can give while, together, we sway to the heartbeat of the African rhythms of life.